In the Pre-dawn October Darkness, JFK Gives Birth to Peace Corps.

Ann Arbor, Michigan — On Oct.14, 1960, I was a young reporter for The Detroit Times covering John F. Kennedy’s Democratic Party campaign for president at a University of Michigan rally.

JFK planned to get some sleep, but as thousands of students and town folks – one estimate put the crowd at 10,000 — wearing Kennedy campaign straw hats and chanting his name gathered outside the university’s Men’s Union, he finally appeared at 2 a.m. His speech is recorded as the birth of the Peace Corps, and a plaque still exists at the now-coeducational Union commemorating that historic moment in U.S. history.

In fact, however, he did not describe what he had in mind as a “Peace Corps” until a Nov. 2 speech at the Cow Palace in San Francisco. But what he did say here became a rallying cry that finally led to establishment of the organization. “I think it could work… building goodwill and building peace,” he said in San Francisco.

JFK paved the way by issuing Executive Order 10924 on March 31, 1961, two months after his inauguration as the nation’s 35th president, asking Congress to pass the Peace Corps Act. It became Public Law 87-293 on Sept.1, 1961, falling under the State Department’s purview with initial funding of $450 million.

Volunteers immediately applied to participate, and the first contingent packed their bags in early 1962. By the following year 5,000 had joined, and during the past 55 years, 225,000 have served in 141 countries. They’ve also been prolific writers; 987 have written books about their Peace Corps experiences, as have 52 staffers.

John Coyne was among the first to embark, for Ethiopia, and taught English in Addis Ababa. In an article published in the January-February 2017 edition of American Diplomacy, Coyne traces the origin of numerous efforts akin to the Peace Corps dating back two centuries, covering both the U.S. and other nations.

Credit for introducing the first Peace Corps legislation, however, goes to Hubert Humphrey, who ran against Kennedy in the 1960 presidential primary, later served as Lyndon Johnson’s vice president, and ran unsuccessfully for president against then-Vice President Richard Nixon in 1968.

Humphrey also served two separate terms as U.S. senator from Minnesota, 1949-’64 and 1971-’78. During his first term, in 1957, he floated a Peace Corps bill, but by his own account “it did not meet with much enthusiasm.” Diplomats “quaked at the idea,” he said, “and many senators, including the liberal ones (like Humphrey) thought the idea was silly and unworkable.” JFK, a fellow Democrat who served in the Senate at that time with Humphrey, apparently was not among the skeptics.

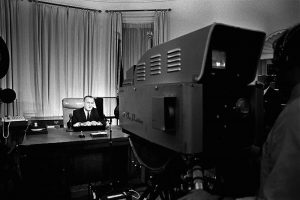

There was little media presence of JFK’s remarks on that brisk autumn pre-dawn morning. Unlike today’s 24-hour pervasive coverage of anything and everything, most reporters thought there was no more news to be made because JFK had said he planned to retire. When he appeared he faced only a single microphone set up by WUOM-FM, the university’s radio station, not the crowded bank that routinely festoon podiums today.

My buddy, Detroit-based Newsweek reporter Hugh Wray McCann, joined me as we jostled our way up the steps of the Men’s Union. Both of us lived in Ann Arbor, 45 miles west of Detroit, which was convenient for our assignment editors. We were also Michigan alums.

Nixon attracted a modest crowd two weeks earlier during a whistle stop campaign speech at the Ann Arbor train station. On the night of JFK’s visit, however, a band of university students built a paper mache mockup of Nixon and set fire to it only a stone’s throw from the Union before JFK made his appearance.

So what did JFK actually say in that wee-hours-of-the-morning address? I had heard him speak many times during his campaign, of course, and was impressed by his youthful appearance – he was only 43 –and his staccato delivery and Boston brogue. Smiling broadly with sparkling teeth, he began:

“I want to express my thanks to you, as a graduate of the Michigan of the East, Harvard University (laughter). I come here delighted to say a few words about this campaign that is coming into the last three weeks. I think in many ways it is the most important campaign since 1933, mostly because of the problem which press upon the United States, and the opportunities which will be presented to us in the 1960s. The opportunity must be seized, through the judgment of the President, and the vigor of the executive, and the cooperation of Congress. Through these I think we can make the greatest possible difference.

(Then he got to the meat of what led to his Peace Corps initiative).

“How many of you are going to be doctors, are willing to spend days in Ghana? Technicians or engineers, how many of you are willing to work in the Foreign Service and spend your lives traveling around the world? Or your willingness to that, not merely to serve on year or two years, but on your willingness to contribute a part of your life to this country, I think will depend the answer whether a free society can compete. I think it can! And I think Americans are willing to contribute. But the effort must be far greater than we have ever made in the past. Therefore I am delighted to come to Michigan, to this university, because unless we have those resources in this school, unless you comprehend the nature of what is being asked of you, this country can’t possibly move through the next years in a period of relative strength. So I come her tonight to go to bed! But I also come here tonight to ask you to join in this effort…This university…this is the longest short speech I’ve ever made…therefore I’ll finish it! Let me say in conclusion, this University is not maintained by its alumni, or by the state, merely to help its graduates have an economic advantage in the life struggle. There is certainly a greater purpose, and I’m sure you recognize it. Therefore, I do not apologize for asking your support in this campaign. I come here tonight asking for your support for this country over the next decade. Thank you.”

Clearly this was a clarion call for Americans, particularly young students, to place duty to country above salaries that might come with their diplomas.

This was cemented when, toward the end of his inaugural speech on Jan.20 1961, JFK admonished Americans to engage in public service and ended with perhaps his most memorable quote: “And so, my fellow Americans. Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.”

Back in October it was too late, of course, to file a story for that day’s Detroit Times, and I am not sure I entirely grasped the significance of the speech when I heard it; at first blush it sounded like a typical message you’d expect a candidate for the presidency might deliver in a college town populated largely by liberal-leaning students.

Within weeks, however, pundits and editorial writers took to their typewriters with a flourish to express their opinions, pro and con.

Although short on specifics, JFK had in mind an army of trained volunteers to work for a few years in underdeveloped countries to help promote peace by working in key areas such as education, farming, health care and construction projects. Basically, it amounted to community service on a global scale designed not only to promote peace but also to bolster the image of the United States. Later surveys indicated that volunteers overwhelmingly thought their service had accomplished those objectives.

It was a bold idea, but Nixon argued that the Peace Corps would merely provide a safe haven for draft dodgers, especially as the Vietnam War escalated. In fact, volunteers were not exempt from Selective Service. U.S. enemies viewed it as a potential spy agency backed by the Central Intelligence Agency. The CIA’s policy, however, restricted volunteers from any clandestine involvement.

Coyne cites an early Gallup poll indicating strong acceptance of the Peace Corps, with 71 percent supporting and 66 percent saying they wanted their “sons” to sign up. Females were not included in the early thinking, but they were in the final Peace Corps bill and today comprise 62 percent of the current 7,213 volunteers.

Parents and others worried about the safety of the volunteers, who often have worked in unstable countries, some led by dictators and rival militias and tribes. And to be sure, there were scandals. Time, in a 50-year review of the Peace Corps in 2011, cited an ABC News 20/20 investigation that claimed 1,000 female volunteers had been raped or sexually assaulted and 23 (of both sexes) were murdered over its first half-century. That’s certainly not a pretty picture but not bad enough to write off the movement. Startled by the 20/20 report, then-Peace Corps Director Aaron Williams promised major reforms.

In fact, at first JFK wasn’t sure the Peace Corps would be successful. That’s one reason he reportedly chose his brother-in-law, Sargent Shriver, to be its first director; he could fire Shriver without much collateral damage in case things didn’t work out. By 1963 Shiver had travelled 350,000 miles and visited 35 countries. He stayed on until 1966.

Over the years, but especially in the early going, the Peace Corps attracted a widely diverse group of individuals, young and old, and from a variety of backgrounds. Among the well known:

- JFK’s grand-nephew, Joseph P. Kennedy III of Boston, who was elected to the House of Representatives in 2012, and served in the Dominican Republic 2004-’06.

- Lillian Carter, the future president’s mother, India 1966-’68.

- Bob Taft, great-grandson of President William Howard Taft and Ohio governor from 1999-2007, Tanzania 1963-’65.

- Christopher Dodd, Democratic senator from Connecticut, 1981-2011, Dominican Republic 1966-’68.

- Chris Matthews, MSNBC commentator, Swaziland 1968-’70.

- Reed Hastings, co-founder and CEO of Netflix, Swaziland 1983-’85.

- Donna Shalala, U.S. secretary of Health and Human Services, 1993-2001, Iran 1962-’64.

- Paul Tsongas, former U.S. senator from Massachusetts who ran for president in 1992, Ethiopia 1962-’64.

Exactly three weeks after JFK’s now-famous speech I received a phone call, also at 2 a.m., informing me my services were no longer required at the Detroit Times. There was no further explanation, leaving me to agitate over what I may have done to merit this summary execution. At 4 a.m., my brother-in-law Frank Tomlinson, then a newsman on Detroit’s powerful WJR-AM, phoned and asked if I had heard the news. What news? “The Times has been sold to The Detroit News,” our arch competitor, he said.

So I left Ann Arbor and I went on to enjoy a long career in journalism that included The Toledo Blade, The Wall Street Journal, The Detroit Free Press and Wards Auto World, an international business newsmagazine.

Although I’ve covered a broad range of stories, including Detroit’s infamous July1967 riot, JFK’s assassination on Friday Nov.22, 1963, stands out. By that time I was a staff reporter for The Wall Street Journal in Los Angeles.

All of WSJ’s bureaus worked over that weekend gathering reaction to this sad, horrific event. In LA we contacted movie stars, who were mostly pro-Kennedy liberals, as well as California’s cadre of notorious right-wingers. The extremely far right John Birch Society, which remarkably once called President Dwight Eisenhower a Communist, had an office in the posh LA eastern suburb of San Marino near Pasadena. I phoned and asked the local JBS leader, a close associate of founder Robert Welch, his thoughts on the assassination. He had a short, terse reply: “The chickens have come home to roost.” The clear implication: JFK, who the Society also deemed either a commie or a sympathizer, had it coming.

By some counts up to 40,000 books have been written about John F. Kennedy and his short, but impact-filled, life as commander-in-chief of the world’s most powerful nation. In that respect, perhaps the Peace Corp should be considered only a lengthy footnote.

But don’t tell that to the legions of Peace Corps volunteers who, over the 57 years since his call to service, have traveled to all corners of the earth, often under extremely trying and dangerous circumstances, to help the less fortunate, spread the message of peace and democracy, and to bolster the reputation of the U.S.A.

By Wednesday, order was close to being restored as we continued to focus on the economic losses. This included scores of businesses owned by both blacks and whites, victims of widespread arson and looting.

By Wednesday, order was close to being restored as we continued to focus on the economic losses. This included scores of businesses owned by both blacks and whites, victims of widespread arson and looting. These operations were replaced with new factories, as GM and Chrysler commited to supporting the city. GM’s Poletown plant straddling the border between Detroit and Hamtramck opened in 1985 and Jefferson Avenue in 1991. Both continue to make cars and SUVs in the city.

These operations were replaced with new factories, as GM and Chrysler commited to supporting the city. GM’s Poletown plant straddling the border between Detroit and Hamtramck opened in 1985 and Jefferson Avenue in 1991. Both continue to make cars and SUVs in the city.

Recent Comments